Working Content

Prerequisites:

| Early in our studies of electric charge we learned that any electric charge (positive or negative) will attract neutral matter by polarizing the charges that the matter is made up of. In the figure at the right, the (fixed) negative charges on the balloon attract the positive charges in the wall and repel the negative ones. (Since in solids the electrons move more easily than nuclei, the negative charges are shown as moving more.) As a result, the positive charges are closer to the balloon and their attraction wins out over the negative-negative repulsion. The result would be the opposite if the charge on the balloon were positive and would still result in an attraction. |

|

The Dielectric Constant

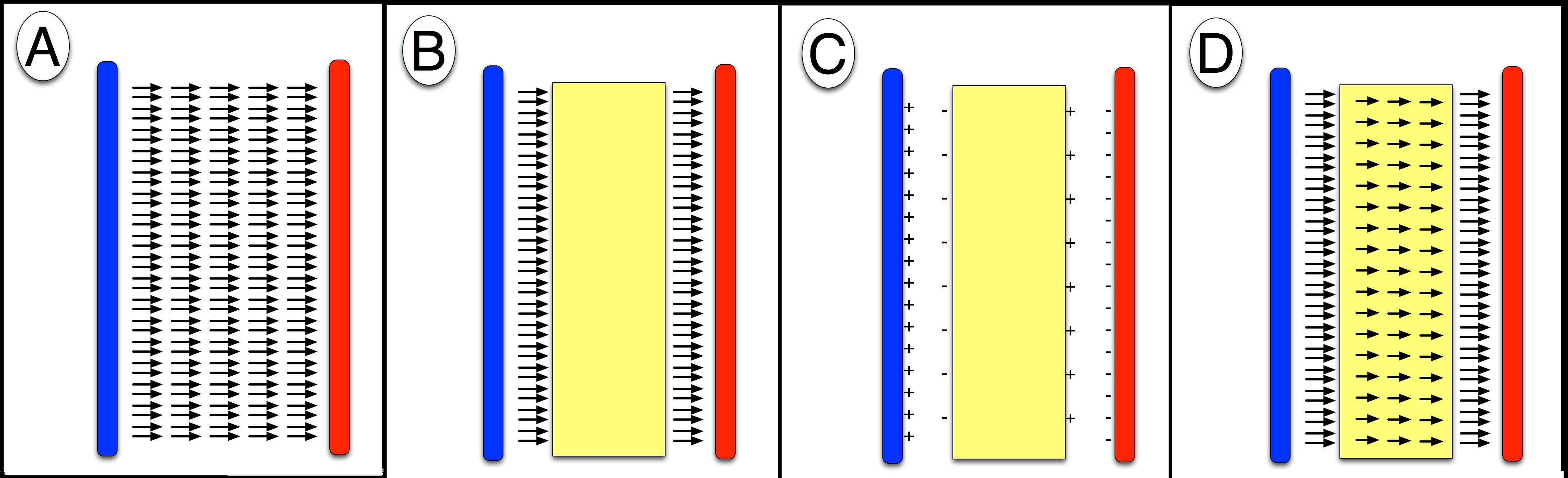

This effect has implications for how our treatment of electric fields and potentials when they occur in matter. To see how this works let's consider a simple toy model - putting some matter into a constant electric field. The easiest way we know to generate a constant electric field is using two plates of equal and opposite uniform electric charge as in our simple model of the capacitor. Let's consider this in 4 steps as in the figure below.

In the first step (figure A) we show the electric field (close to uniform) produced between uniformly charged sheet of positive (blue) and negative charges. In the second step, we introduce a block of insulating matter into the field. The positive charges on the left and the negative charges on the right polarize the matter, pulling negative charges to the left and positive charges to the right. Since the matter is an insulator, the charges typically don't move very far. In the middle of the block, the shifting charges cancel out, but at the edges they don't. (See the picture of the balloon above.) In figure C we show the result of the charge distributions. (In this figure we show the charge distributions on the outside plates as well, which are not displayed in the other figures.) Since charges don't move very freely in the insulator, the amount of charge pulled to the surface is less than the amount of charge creating the original field.

These charge on the surface of the insulator act like two new parallel plates. They produce a uniform field between them. But because of the orientation of the charges, the field is in the opposite direction from the original field and not as strong. The resulting field is the sum of the two. Outside of the insulator the field is as before. Inside, it is reduced. (Remember that the field is 0 outside of two oppositely charged parallel plates.) The resulting field is as shown in figure D. Strong on the outside, weaker on the inside.

The ratio of these two fields depends on how easily charges move in the insulator, so it is a property of the particular kind of matter it is. The dimensionless reduction factor is called the dielectric constant and is (in physics) usually written with the Greek letter kappa (κ):

Einside = Eoutside/κ

Note that the dielectric constant goes underneath the outside field, so to make it smaller, κ is usually greater than 1.*

Implications for capacitors

The important thing about a capacitor is the amount of charge separation that can be stored for a given potential difference. The charge separation can serve as a battery and provide an amount of current flow. The potential difference measures the amount of work that has to be done to charge a capacitor. So when we write the capacitor equation

Q = CΔV

a bigger C means that we can get more current out doing less work -- a more effective capacitor.

Since ΔV is the E field times the distance (or, better, the E field integrated over the distance), if we reduce E inside the capacitor, we reduce ΔV. The result is that if the capacitor is filled with an insulator of dielectric constant κ, the capacitance will be increased by that factor. For a parallel plate capacitor filled by an insulator, the capacitance will become

Same as before, but not with an extra factor of kappa.

What about conductors?

What if instead of an insulator we put a conductor in between our parallel plates? Then in figure C, the charges drawn up on the outside of the conductor would be equal to the charges on the original plates. The back-field produced by these new charges will be equal and opposite to the original field and the field inside the conductor will go to zero. This makes sense; if there were any field inside the conductor and if there were movable charges, the field would cause them to move. So the field causes them to move so that they build up a back field and they continue to do so until it has cancelled all the field inside the conductor. Then there is no more reason for charges to move.

Since the field inside the conductor is now 0, it implies that the dielectric constant for a conductor should be taken to be infinity. (If we look at oscillating electric fields the situation becomes more complex.)

* Another reason for this is that if the Coulomb constant kC is written (as it sometimes is) as kC=1/4πε0 then κε0 are sometimes combined as ε=κε0. Then Coulomb's law for an electric field of an external charge inside matter can be written the same as in free space but with ε in the Coulomb constant instead of ε0. It will then include the effects of polarizing the medium. Note, however, that in some chemistry and biology texts, "ε" is used to stand for "κ". This is an abomination since then the symbols "ε" and "ε0" which appear in the same context have different units. (You often see things like εε0 in a single equation to mean κε0. It is then very difficult to keep units straight.)(I know that physicists do this too -- as for example using k to mean a spring constant, Coulomb's constant, Boltzmann's constant, and a wave number, each of which have different units. This is bad too, but usually these occur in different contexts so you can tell what the appropriate units are.)

Joe Redish 2/27/16

Comments (0)

You don't have permission to comment on this page.